Bruce Ames’s family genes are deep in two things—engineering and the Navy. His engineer father and brother-in-law were Navy, and this family history inspired him to pursue and earn a four-year scholarship to Maine Maritime Academy. This is where he received a degree in marine engineering technology and acquired a Coast Guard license. He was commissioned by his Naval officer brother on graduation day, and shipped off to a three-year duty aboard the USS Forrestal.

The 1,100-foot aircraft carrier was made famous when it caught on fire in July of 1967, triggering a chain-reaction of explosions that killed 134 sailors and injured 161. At the time, Forrestal was engaged in combat operations in the Gulf of Tonkin, during the Vietnam War. The ship survived, but with damage exceeding US$72 million, not including the damage to aircraft. Future United States Senator John McCain and future four-star admiral and U.S. Pacific Fleet Commander Ronald J. Zlatoper were among the survivors.

Ames served his time on the Forrestal from 1989 to 1992, more than two decades later, but some of the explosion damage left challenges for the future engineers and operators.

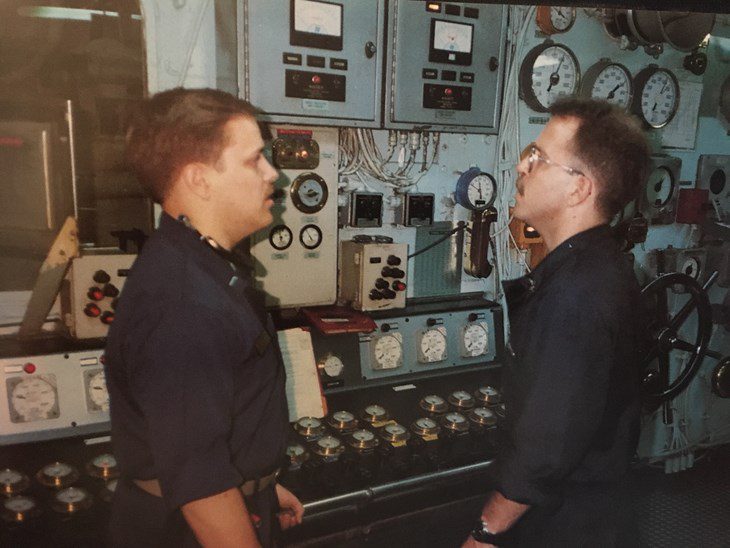

“I worked with pumps, valves, steam generators, turbines, and had 110 boiler technicians and machinists who reported to me in his division,” Ames recalled. “This represented only half of the engineering department on the ship. More than 5,000 people were onboard, and sometimes we had 90 planes onboard. About 3,500 people were stationed on the ship full time. On the ship, we did not design anything. But as an officer and head of the engineering department, we were in charge of everything that keeps a ship running.”

The Forrestal had four main steam engines, eight boilers, and eight generators. They would convert salt water into fresh water, and supplied the steam to the catapults to launch the planes. They also maintained the air conditioning and heating units for the entire ship.

Challenges on Board

The Forrestal was built in 1954. It was the oldest still-active aircraft carrier in the Navy at the time of Ames’ duty.

“Anyone who goes into the Navy and into fire-fighting school studies the fire incident on this ship to learn what they did wrong and what they did right,” Ames explained. “The biggest challenge for us was that it is an old ship, so there was a lot of old equipment to keep running.”

Ames scheduled all the routine maintenance. At dry dock, his team would perform the major repairs. With a young crew right out of high school, and since there was an active war, drills happened every night to ensure the crew and the ship were combat ready.

Now, nearly 30 years later, Ames uses this experience as a lubrication engineer with ExxonMobil. He currently helps his customers solve problems through lubrication strategies and vibration analysis.

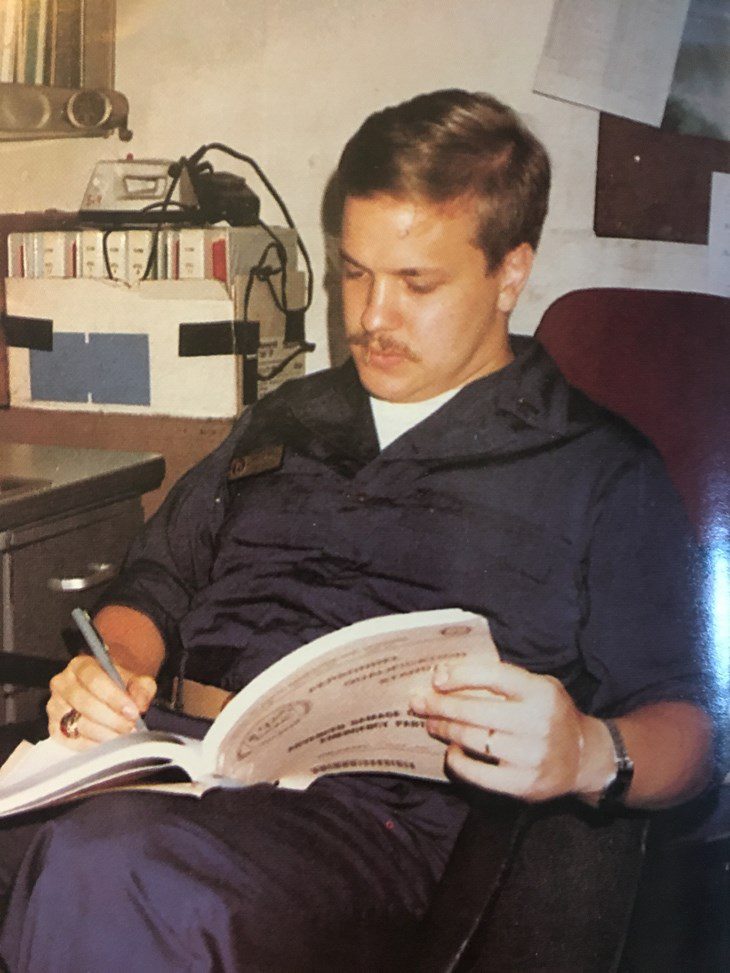

“In the Navy it is different than in industry,” he explained. “Every maintenance practice is documented down to the most minute detail. We had cards that described procedure, including tools needed, and full instructions – step, by step, by step. Everything was documented. I kept the schedule up to date, and the chiefs assigned the work.”

After his second year onboard, the military introduced vibration analysis as an activity to be performed on the ship.

“We were the first ship to perform vibration analysis for rotating equipment, and I was the officer in charge of the analysis team,” he said. “So I was trained in this area. I then evaluated all the data and reported to the chief engineer. Vibration can be predicted long before you ever see it or feel it. For example, one of our main generators had a phenomenon called oil whip. The bearing had worn to a point where the oil was holding onto the bearing and whipping around the shaft. I told the engineer, but he was hesitant about the new technology. I knew that catastrophic failure was eminent because I believed what the data was telling me. Now, this technology is used routinely in every paper mill that I go into. Years ago, it was cutting edge technology.”

Onboard, there was some inventory of equipment and spare parts. They also utilized a full machine shop. “If it was something we could make, we had the ability to make it in house,” he said. “Just like the merchant ships like the freighters and the tankers that go overseas all the time, they have a full machine shop. In college I learned welding and other machine shop skills. When you are at sea, you must be able to fix almost everything yourself. Unless there was a certain piece we did not have or could not make, we could get it flown in. We had four engines, so we could run on one main engine if we had to, whereas a Merchant ship usually only has one engine. If their engine goes down, they are dead in the water.”

Experience after the Navy

After the Navy, Ames returned to the northeastern United States and got a job with his father, who was a branch manager for an industrial pump distributor. He later landed a job with a lubricant distributor as a lubrication engineer for heavy equipment. He did that for 10 years, working in many industries including paper, power, plastic injection molding, and shipping. During that time he also managed major reclamation efforts with trucks cleaning customers’ oil in industry.

“We had to remove water and dirt from the oil,” he said. “We would clean reservoirs, and do initial fills for power plants. I performed a lot of engineering work and helped to train the other salesmen. I was the licensed engineer on staff so I would visit customers and do lubrication training all over New England and New York.”

Working for another major oil company for seven years, he was on the CVL (Commercial Vehicle) team for five years handling all the large fleets for FedEx, Estes, JB Hunt, Ryder, etc. Four years ago, he started working with ExxonMobil.

Problem solving with ExxonMobil

Ames is now the technical lubricant expert for his area of Wisconsin and the Upper Peninsula of Michigan.

“I meet with companies of all sizes in all industries,” he said. “I develop a business plan each year to see what our Mobil Serv approach can do to help save customers money for the next year. For example, I may create a leak detection program that provides data about savings that can be achieved over a period of time. I work on air leak detection, bearing and gearbox inspection, and failure analysis. I tell my customers that if you buy Mobil lubricants, I become your pre-paid consultant engineer to help you be more profitable any way I can. So they use me as an engineer to help in any aspect with lubricants and equipment reliability.”

Ames’ early experience with vibration analysis has come in handy.

“With my vibration analysis background and pump background and paper industry background, my customers can look at me as an additional set of eyes that is not there everyday,” he said. “I sometimes see things that other people cannot see because they are looking at it every day.”

Ames recently worked on a steam turbine generator at a paper mill where the hydraulic system that operates the throttle valve on the steam turbine has varnished through the years and was starting to stick.

“This was preventing the turbine from performing properly and causing it to trip out,” he explained. “I sat down with the customer and recommended an ExxonMobil system cleaner, which is a detergent that can be added at low doses over time so you can keep running the equipment. It will slowly clean the system internally and clean the varnish off the valves. You can run it for three to four weeks, then on a scheduled shutdown, we can pump out the oil from the reservoir and fill it with a high efficiency hydraulic oil, which has a keep clean technology. It will not varnish over time like the previous oil they were using. This makes the turbine much more reliable and makes the valve operate properly.”

Practical Tips

Sometimes Ames’ projects are complicated, and sometimes there are simple solutions.

“Something that is gaining some traction in the industry is the fact that centrifugal pumps only hold a few gallons of oil,” he explained. “Formerly, the OEMs would advise to change the oil every six months . . . kind of like changing car oil every 3,000 miles. You really don’t need to do this any more as long as the oil is staying clean and dry and the seals are working properly and not getting contaminated. The oil will last longer. I have many customers now who are filling their pumps with synthetic oil. In the auto industry, they are going all synthetic because of demands for higher fuel efficiency. Synthetic oil will make your pumps use less energy. The motor will work more efficiently and you can save one and a half to 4 % of your electric bill if you use synthetics in your pumps.”

He explained that the higher cost of synthetic oils is offset by the benefits.

“You can go five years without changing synthetic oil as long as you check the site glasses and ensure the oil is clean and dry and no water or dirt is getting in. You will pay less for the more expensive oil because you are not changing it as frequently. Also, you will save electricity. You will also have 20 to 25% better wear on the bearings, so the pumps will last longer. It is a triple whammy. This is the kind of reports we provide that show the total cost of ownership.”

Ames also offers practice advice with specific regard to valves.

“With regard to lubrication on most industrial valves—whether it is a gate valve or a globe valve—most have a grease fitting to grease the threads,” Ames said. “Most people don’t grease them until they stop working. You should have a routine maintenance for your valves and have a good lubrication maintenance schedule to make sure they are greased regularly, opening and closing the valve to ensure that when they are operating the valves will move.”

In daily life, Ames reverts back to lessons learned from his father long before he was a naval officer or a lubrication expert. “The biggest lesson I learned from my father was to always be honest with the customer. If you don’t know, don’t give them an answer and get back to them. And always be fair.”