In the overall selection process for installing industrial valves, a fusion joining process is often chosen for reliability and simplicity reasons. Generally, there are three processes that can be used when joining valves to pipe or tube. The connection type on the valve will often provide guidance on which process is the most suitable. Once the joining process is selected, it is important to consider the effects of the energy input into the chosen valve.

By Fred Schweighardt, Director of Business Development, Advanced Fabrication Markets and an International Expert for Airgas, an Air Liquide Company

One of the most common processes used to join valves and pipes is fusion welding, which uses a variety of arc processes. Brazing is most often done with an oxy-fuel flame and high temperature filler material. For lower pressure service, the typical practice is soldering, which uses an air-fuel process and a lower temperature filler material. Technically, brazing and soldering are not ‘fusion’ processes, but may be considered as such for the purpose of this discussion.

The connection type on the valve will typically indicate which process is the most suitable. For example, a brass valve with a socket weld (SW) connection would suggest brazing or soldering as the joining method.

Types of Welding and Brazing Processes

Common welding procedures for the process piping industry include: Gas Tungsten Arc Welding (GTAW), Shielded Metal Arc Welding (SMAW), Flux Cored Arc Welding (FCAW), and Gas Tungsten Arc Welding (GTAW). The brazing process is defined as a fusion method that uses filler metal with a melting point above 840°F. The filler metal is drawn into the faying surfaces of the joint by capillary action. Soldering is much like brazing, except that the filler metal melts below 840°F.

Any of the listed processes will introduce heat into the body of the valve and will result in two main consequences: damage to the ‘soft’ components and distortion of the valve body itself. The risk of damage depends on the heat input and the material of the valve. To minimize the probability of damage, there are a number of procedures that can be implemented. Therefore, it is important to review the end-connection types and discuss the usual joining process, concerns and mitigation techniques.

Socket Weld (SW) Valves

This valve type has a cavity that is sized to accept the appropriate size piece of pipe or tube. The pipe is inserted into the socket and then joined using one of the listed processes. ASME B31.3 requires that the pipe/tube be inserted into the cavity to a point that allows a minimum of 1/16” between the end of the pipe and the bottom of the socket. This gap allows for the contraction of the weld that is applied to the joint interface and prevents the stress on the valve body that would be present if the tube was bottomed out.

The contraction of the weld is less of a concern with the brazing process, and even less with soldering. However, as with any operation that involves energy input to a valve, some precautions must be taken to prevent damage. Any elastomeric materials, as most of these materials are not heat resistant, are subject to relatively low levels of heat input and can compromise the sealing and external leak-tightness of the valve. If using a brazing or soldering method, the operator should monitor the amount of filler material used in order to minimize internal protrusion that can occur with excess filler metal use.

Butt Weld (BW) Pipe & Tube Valves

These valves are often intended for somewhat more severe service, and potentially higher pressures. The valves come in two general configurations. The first configuration are valves that are machined on the inlet/outlet with the typical pipe end prep. The second configuration consists of a SW valve with stub ends that are installed by the manufacturer.

The first type of valve can be more challenging to successfully weld, as the weld end is close to the working parts of the valve, so elastomer damage and body distortion due to heat input are much more likely to occur. This type of valve would not be suitable for the brazing or soldering process, so fusion welding is typically used. If the valve has a heavy wall at the weld end, the issues become even worse, as many passes are needed to fill in the joint. In this instance, it is pertinent to remove the soft seals and seats and consider controlling the heat input for the duration of the weld to minimize distortion. Common heat input limiting measures include: stringer passes instead of weaves, low interpass temperatures, active cooling of the valve/weld area and low heat input weld processes.

The second configuration is relatively low-risk in terms of heat input, as the stub ends are far enough from the affected parts of the valve body to prevent much heat transfer. Tube-end valves are also considered butt-weld, but these types are often welded automatically with an orbital system. The tube wall is fairly thin, and the automated system performs a complete penetration weld very rapidly, which limits the heat input. In addition, the tube-ends are generally fairly long, and therefore are located at a good distance from the valve, which further assists in reducing how much heat reaches susceptible parts. In the rare cases where the tube-end valves are welded manually, some control over the heat input must be exercised. In tube-end or BW end valves, it is also important to be cautious about the internal protrusion of weld that results from a completely welded butt joint. There are code requirements on how much that protrusion can be, and in general, the lower the protrusion the better, as long as the weld is properly made. Excess penetration can reduce flow capabilities, and in extreme cases, introduce large particulates into the valve body, which could then damage the seating materials.

Heat Input

As has been detailed in the previous paragraph, one of the most important things to consider is heat input. Heat input can be calculated with a standard formula, which will help establish what level of concern is necessary. The formula for heat input is:

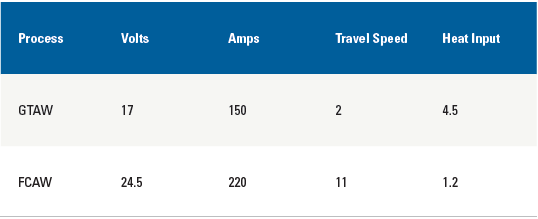

For example, it is interesting to compare GTAW and FCAW to see which provides a lower heat input.

In this example, there is a NPS 2 S80 butt weld valve and a weld length of ~6.8” with a wall thickness of .218in. A standard 75° joint prep has a weld volume of ~.632in3 and a mass of .18lbs. Common deposition rates of GTAW might be 1 lb/ hr and FCAW could be ~6 lb/hr.

The FCAW process would only need about two minutes of arc time, and the GTAW process would take at least 10 minutes. If the following input parameters are used, the massive impact that the increased travel speed has on reducing heat input becomes apparent. This decision may point the operator to choose to weld the valve with FCAW, perhaps using the roll-out method (1G) on a spool, and then using another method in the field for the tie-in. This would give the advantage of a high-deposition process that has a low inherent heat input for welding of sensitive parts, such as a valve.

Final Thoughts

The protection of the valve components, whether the soft goods or the integrity of the body, are important when a joining process that adds heat to the component is used. Mitigation procedures include removing vulnerable materials, selecting low heat input processes and techniques and welding as far as possible from the sensitive areas. Active cooling (when qualified as part of the procedure) can prevent heat damage as well.