By Brittani Schroeder and Angelica Pajkovic

Gary Boles was drawn to engineering at a young age, and pointed his high school education towards ultimately achieving a degree in that field. His older brother, who has a PhD in Chemical Engineering, was also a positive influence on his decision. “I think a person has to be born with a certain kind of acumen to choose engineering as their profession,” said Boles. “They need to have the right mind to deal with the things engineers have to deal with.” After achieving his Bachelor of Science in Mechanical Engineering from the University of Tennessee, Boles worked in the power industry for thirty-one years as a utility employee.

Boles was drawn to the power industry because of the fascination it held for him. “It was not the money, nor was it the glamour. There is nothing glamorous am in the power industry helping to create something that everyone needs is pretty cool.” He spent three decades working at Tennessee Valley Authority in their nuclear power program. He acted as First Line Maintenance Supervisor and worked his way up to an Engineering Manager; his experience has been primarily in maintenance and engineering of mechanical components.

For the last decade, Boles has worked as the Principal Technical Leader at the Electric Power Research Institute (EPRI). His primary focus has been to help improve the reliability of power plant equipment through improved processes and work practices. “I feel like I am making a difference,” Boles said.

The Collaborative Model

Boles spends a lot of his time trying to find long-term solutions for problems that arise in the industry. “When you are busy, it is easier to throw a Band-Aid solution on a problem and move on, but that will not give a stable solution. The problem will happen again and again, and that is why I am here: to stop the problem,” he explained.

One of the aspects Boles enjoys most about his job is being presented a challenge, and then being able to solve it. “I get presented with problems that have been quite difficult to solve in the industry,” said Boles. “After I am given the issue, I work alongside my coworkers and we find a solution.” Using the collaborative model, Boles and his team work with people at the utilities, manufacturers, vendors, service providers, and whomever else they can think of to find the resources to resolve the issue. “The people I work with have so much experience, which means we can all bounce ideas off each other and step up when someone needs help. It is a great team to work in,” Boles said.

Gary Boles and his team like to call themselves the “plug and play” guys. “Our boss can ask us to do anything, and he knows we will get it done. Sometimes our boss does not even get involved because he knew he does not have to. We are all pretty seasoned employees,” he said.

Challenges to Innovation

“The nuclear power industry sometimes stifles innovation,” admitted Boles. He has always understood why this challenge occurs: the people in the nuclear power industry are working in a highly regulated environment, or an environment where there is a risk of plant events that could affect the public so strict standards are set to ensure safety. Sometimes innovation also comes at a financial risk, and it is hard to embrace a new idea or new way of thinking or working.

EPRI encourages innovation, and Boles was happy to make the career move to be more of a researcher. “It is really the best job I have ever had,” he said.

Nuclear Power Plant Pumps

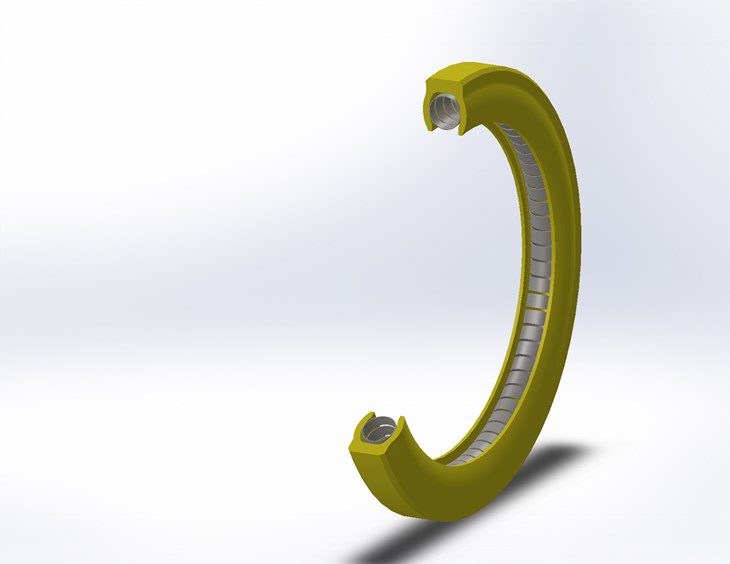

“One of the most recent projects I have been working on deals with pumps,” Boles explained. “We were working on a seal that could have its physical dimension changed based on operating parameters of the pump while it was running.” As in most cases nuclear power plants use mechanical seals, Boles has had a lot of experience working with them.

The challenges Boles faces most often are problems with mechanical seals. He spends a lot of his time researching why a seal might fail and how the plant can fix the issue. Another challenge he faces is corrosion of raw water pumps. “In our industry, many of the pumps are getting quite old, and there is therefore a whole host of problems that can occur. Examples include MIC (microbiological induced corrosion), general corrosion which happens over time, and sometimes there are issues that do not become apparent until there is major damage,” said Boles. “At that point, you are trying to determine the best repair method.” If there is damage to the impeller or shaft, it is hard to replace because of how large and expensive the parts are; to mitigate the extra expense, Boles suggests trying to repair before replacing the part.

“If I had to choose, I would say working with mechanical seals is a little more challenging than most other applications, so it is my favourite to work with,” Boles explained. “Mechanical seals move, and there are more dynamics involved. I have loved learning more about them in my role at EPRI.” Leakage of radioactive fluids from nuclear power plant pumps is important from a radioactive contamination and dose perspective. In addition, excessive leakage can affect the reliability of the pump to provide a safety function or just to be used to produce power, so seal performance is important. One of the areas we are seeking to exploit is the use of new technologies to monitor the performance of mechanical seals to mitigate failure or to determine when seals require maintenance so that it can be performed during planned outages rather than forced shutdowns during high electric power demand seasons. The desire to improve performance while reducing operating cost has become more important for nuclear power plants in recent years due to the competition from other power sources. However, the large base loads that nuclear power plants provide make them important to the overall electric power supply suite of plants (e.g. coal fired, gas fired, co-generation, and renewables such as wind and solar).

The Exploding World of Valves

When speaking about valves, Gary Boles’ primary focus is valve packing. “Valve packing sounds simple, but it tends to get pretty complex because it has to seal the valve. It cannot have too much friction however, as that would make the valve difficult to operate,” explained Boles. There are a lot of margin issues with valves in the nuclear power business. The design side of the business wants to make sure the valve will open, close, and be safe to use, but the people working with the valves want to make sure they are packed, sealed, and will not leak. So, the question Boles and his team try to answer is how can valves be approved by both sides?

“I am currently working on a project to improve the use of PTFE Teflon,” said Boles. “PTFE is not very radiation resistant, but we think we found a way to make it more so. If we can, then we can make some packing out of that improved material.”

Boles is also contemplating a project with squib valves. “Squib valves are cool because they are opened and closed by explosives,” Boles explained. If the explosive goes off in an emergency situation, in order to immediately open or close a valve, technicians must go in and disassemble it and manually replace it, or manually open it to replace the charge. “Typically, these explosives go off to either supply water in an emergency, or to shut off all flowing water. Although used to a limited extent in existing plants, they are used more extensively in the new design plants, like AP1000s,” said Boles. He likes to call squib valves “the best friend he has” in an emergency. He does not want to use them, but if he has to at least he knows it is for sure going to work.

Fatigued Hoses

When Boles worked for TVA, he interacted with hoses on a frequent basis. “They are part of leak control,” he explained, “a fair amount of our time was spent making sure the hoses were not failing due to aging or fatigue.” Boles likened the scenario of a fatigued hose to a traditional metal coat hanger: “If you just bend it back and forth, over and over, eventually it will break. The same thing happens to hoses, so we spend a lot of time making sure that will not happen.”

In Boles’ research role, he receives many questions about problems in nuclear power plants, and he has to find and provide the answers. The main questions he tends to ask are, can an issue be fixed? and can the hose be patched up? or does a new hose need to be bought to replace the one the failed?

Quality Above All

EPRI has qualified a fair amount of the non-destructive examination techniques that are used in the world today. “We have a large contingent of people that work with companies or utilities to qualify processes for non-destructive examination,” explained Boles. “We have a quality assurance program, but it is nothing like what the utilities have with the manufacturers. We just want to make sure our research has intellectual and technical quality to it.”

The Cost of Clean(er) Air

“The nuclear power industry in North America primarily consists of aging plants,” explained Boles. Power plants in the United States and Canada are primarily over forty years old, and the only place new plants are being built is abroad such as China, South Korea, India and the UAE (except for Vogtle 3 and 4 in the southeast United States). There is discussion about building small modular reactors (SMRs) in the near future.

“The cost of repairing or replacing the components found in a power plant can be quite high,” Boles admitted. “If you think about it, the coal plants used to be the big competitors. Now, because of environmental concerns, coal plants are not the competitor that they used to be; individuals are looking for cleaner air, so gas fired plants and renewables have become the major competitors.” Building costs and repairs are high because of how large each nuclear plant is. A lot of time and effort is put into ensuring that the best price is secured for repairs on old plants.

Lived Experiences

An additional reason Boles was excited to work at EPRI was because it provided him with the opportunity to help bridge the knowledge gap present in the industry. As an experienced engineer, Boles spends a large amount of time revising old guides and creating new guides on emerging techniques and processes. “We try to get all that knowledge written down for the newcomers,” said Boles.

“Everything used to be written down in guides. I still spend time writing them, but now we have also started creating instructional videos and interactive software applications, even some virtual reality,” Boles explained. “The young man or woman does not want to sit down and read a two-hundred-page document. They want to watch a YouTube video.”

Boles remembers being young and new to the industry; he made mistakes and it was a great way to learn. “We were all young once, and we were all bound to make some mistakes. The tolerance for making mistakes was a lot higher than it is now. So, we learned the hard way, and we are trying to get our knowledge out there so that the new people will not make the same mistakes we did.”

The low tolerance for mistakes impedes learning. Without the chance to make mistakes, the new engineers do not have the same opportunity to learn and fix their errors. “I try to get down my personal experiences into the guides. If it feels more like a lived experience, and maybe the new people will learn from it a little easier,” said Boles.

Uncertainty Ahead

When Boles began his career in the power industry, he knew he wanted to stay there for a long time. “Something you see a lot these days is new engineers moving around from company to company, or even switching industries,” Boles explained. “Right after they have completed their training they move on to something else. It is difficult when you put a lot of effort into training someone and then they go away.”

Boles knows that a lot of people coming out of school are “chasing the money,” which is different from when he left school. His suggestion for large companies within the industry is to attempt to accommodate the incoming youth. Rather than hold on to past ideals and practices, Boles suggests learning to adapt for the new generation. “It is not very glamourous work, but we have to keep it interesting for these new graduates,” said Boles. “We have to make them feel like they are creating something important, and we are, we are creating power.”