After weeks of tension and military buildup near the Russia-Ukraine border, President Vladimir Putin made clear this was no bluff when he invaded Ukraine land,

air, and sea. What is his goal? Are we watching the early stages of a conflict that can drag the world to WWIII?

Read on to learn how the change in geopolitics might reverberate in the energy market, and consequently, in the valve market also.

By Davi Sampaio Correia, Technical Consultant

Why did Russia Invade Ukraine?

In his speech to justify the invasion1, Putin begins by putting history on Russia’s side – the land where Ukraine sits was once part of Russia since at least the 17th century. Even the modern understanding of Ukraine was Lenin’s invention, who created arbitrary internal borders to facilitate the ruling of the Soviet Union. Closer to the end of the speech, Putin arrives at what is really the crux: NATO expansion.

Imagine Russia acquiring a military base right next to the United States. What do you think the U.S. would do? Actually, you do not need to think, for that really happened in 1962 when the Soviet Union placed several medium-range ballistic missiles in Cuba. According to former Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev, the missiles would serve to deter further American aggression – remember, the U.S. had tried to oust Fidel Castro in 1961 with the Bay of Pigs fiasco. Putin looks at Ukraine and feels the same way Kennedy felt in 1962.

Figure 1 shows a map of Eastern Europe and Russia. The beige/brown areas on the left side of the map are the Carpathian Mountains. Sandwiched between the mountains and the Baltic Sea is a corridor of flat land that Napoleon and Hitler used to invade Russia. On that corridor (and flowing from it) you have Ukraine (not a NATO member) and Poland, Belarus, Lithuania, Latvia, and Estonia (all NATO members). Putin came to power as prime minister in 1999, too late to block some former Soviet states to join NATO (Lithuania, Latvia and Estonia joined in 1991; Belarus joined in 1994). Still, he has made clear that he will wreck Ukraine before it can join NATO.

Aside from the NATO threat, conquering Ukraine has other advantages for Putin. Russia is almost a landlocked country, with only three alternatives to access sea trade. One is through the Black Sea and the Bosporus, a narrow waterway controlled by Turkey that can easily be closed to Russia. Another is from St. Petersburg, where ships can sail through Danish waters, but this passageway can also be easily blocked. The third is the long Arctic Ocean route, starting from Murmansk and then extending through the gaps between Greenland, Iceland, and the United Kingdom.2 To better control access to the Black Sea, Russia went to war with Georgia in 2008 and annexed the Crimea region in 2014.

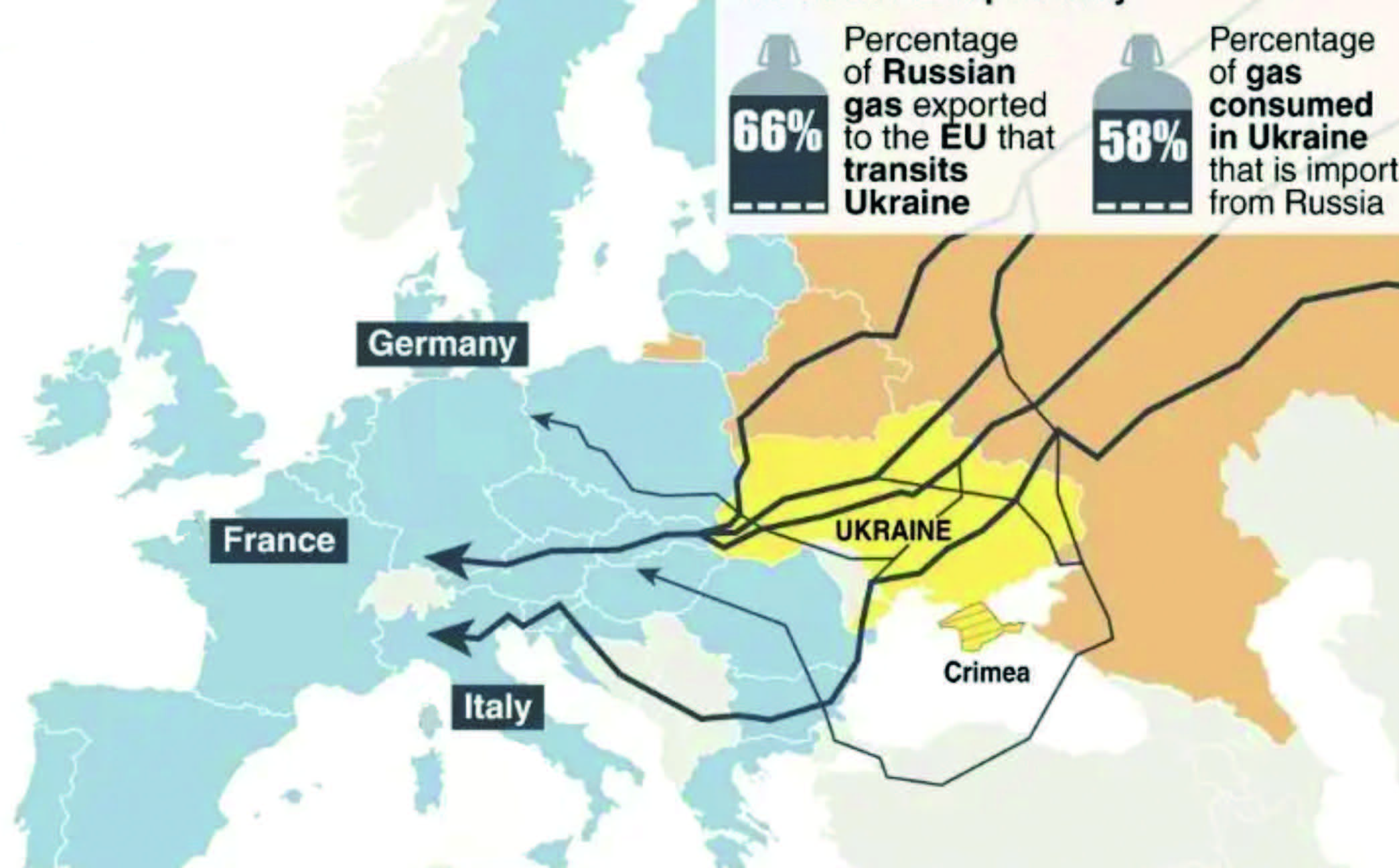

Finally, there is the question of gas pipelines. Oil and gas account for about 25% of Russia’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP) and up to 60% of Russia’s exports. If we look at Figure 2, we see that much of the gas is exported to the EU pass through Ukraine. Gaining control of Ukraine gives Russia more control of the distribution network.

Where Do We Go from Here?

The invasion of Ukraine reminds the world that geopolitics and balances of power still matter in the 21st-century. Due to the sheer weight of men and materiel, one might expect Russia to win this war. But what is there to ‘win’ in the case of occupying Ukraine? That means several possible scenarios:

1. Russia gains control of the whole of Ukraine and installs a puppet regime.

2. Russia gains control of the eastern half of Ukraine (where most of the population are Russian speakers) and annexes it.

3. Russia fi nd itself in a new Afghanistan and resorts to turning every city to ruble.

4. Conflict spreads to Finland and Sweden (for example) and WWIII begins.

5. Russia decides that Ukraine is too much trouble and leaves the country with some consolation prize (more land carved out of Ukraine, a compromise to not join NATO, etc.).

Of all these scenarios, number 5 and number 2 are probably the most realistic ones. Remember, if the basic reason for invading Ukraine is to prevent it from joining NATO, the message was received for all involved. So, if Putin can leave Ukraine with something to show for it, he probably will (as he did in 2014).

As for WWIII, which country is willing to commit to that? The United States core strategic interests are the Western hemisphere, Asia, Persian Gulf, and Europe. Of all those regions, the one currently requiring most attention in Washington is Asia, due to the increasing economic and military capabilities of China. The recently released Indo-Pacific strategy states that very clear:

“This intensifying American focus is due in part to the fact that the Indo-Pacific faces mounting challenges, particularly from the PRC. The PRC is combining its economic, diplomatic, military, and technological might as it pursues a sphere of influence in the Indo-Pacific and seeks to become the world’s most influential power.”3

China also has strong economic ties with Russia and has remained largely neutral. Beijing, for the moment, is not interested in damaging even more of its reputation with the West. “And China, like the rest of the world, will face inevitable economic and geopolitical fallout, including from Western sanctions against Russia and a spike in energy prices”.4

That leaves Europe. Direct intervention in this conflict is highly unlikely due to Europe’s dependence on Russian gas (See Figure 3). On average, gas from Russian accounts for 30% of the European Union (EU), but when we look at individual countries, we see that half of the gas consumed by Germany comes from Russia. Germany is the largest economy in the EU and any decision on war needs their support.

The main response the world has given to Putin’s aggression is in the form of sanctions. The U.S., Canada, Japan, Australia, and the EU have already announced a host of sanctions affecting basically banks (blocking access to the SWIFT international payment system and freezing assets) and technology (restrictions on semiconductors, telecommunication, navigation, and avionics, to name a few). Sanctions alone might not be sufficient to force Russia to back out, as Cuba, Iran, and North Korea may at-test. However, the burden of sanctions in conjunction with Ukrainian resistance and the costs of modern warfare might prove to be an efficient combination.

In the meantime, oil and gas prices have gone up and they will stay up if the conflict sees no resolution. WTI crude futures have recently crossed the $100 barrier for the first time since July 2014 (and it is worth remembering that on July 2014 hostilities between Russia and Ukraine were on the news; that month saw the downing of Malaysia Airlines Flight 17 by a Russian anti-aircraft missile, killing all on board).

Consequences for the Energy Sector (and Valves)

Modern economies are energy-hungry economies. The more a society relies on energy to function, the most disastrous are the consequences of disruptions. In other words, modern economies need to ensure energy security, that is, to make a country or region more robust to energy disruption by diversifying its primary energy supplies.

In the case of the EU, for example, investments on LNG regasification terminals may be more incentivized by different governments, as LNG can be readily integrated in the existing gas network. If the EU signals more interest in LNG, exporting countries will on the other hand have incentives to build more liquefying facilities and shipyards to build more transporting vessels. That is to say, the situation in Ukraine might act as a boost for investment in LNG.

The COVID-19 pandemic had major impact on some supply-chains and, as a result, many companies started to contemplate plans for reshoring. Reshoring is the process of bringing factories and plants back to the company’s original country. Not many companies moved plants to Russia, but many moved them to China. Given the announced Indo-Pacific strategy by the United States, and the fear that China tries something bellicose against Taiwan, reshoring trends may be on the rise for the next years.

A third consequence of the invasion is more doubtful, but still worth considering. Concerns over climate change have driven many countries to pursue renewable energy sources. Chief among them is Germany, with “Energiewende,” the policy supporting the country’s planned transition to a low-carbon future. Some goals in this policy involve a nuclear phase-out and heavy investment in renewables, such as solar. The problem is that these goals left Germany with one of the highest prices of electricity in Europe and it is affecting its industries’ capacity to compete (the population is also not so happy with the utilities bill).

In conclusion, a by-product of the conflict in Ukraine might be a review of that and other ambitious policies that aimed to reduce emissions with unsustainable practices. Mind you, climate change is a very real problem that needs to be addressed, but a look at past energy transitions shows that they happen over decades. It takes time to develop new technologies and create the associated infrastructure to distribute new sources of energy. When it is done hastily, one might fi nd oneself in Germany’s present position.

REFERENECES

1. http://en.kremlin.ru/events/president/news/67828

2. https://www.forbes.com/sites/

johnmauldin/2016/02/26/10-maps-that-explain-russias-strategy/?sh=19111ac723ec

3. Indo-Pacifi c Strategy of the United States, February 2022, available at https://www.whitehouse.gov/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/U.S.-Indo-Pacifi c-Strategy.pdf

4. https://www.latimes.com/opinion/

story/2022-02-27/russia-china-alliance-ukraine-invasion?consumer=googlenews

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Davi Correia is a Senior Mechanical Engineer who has worked at a major Brazil-based oil company for the last 15 years. Correia is part of multi-disciplinary team that provides technical support for topside piping and equipment of production platforms. During this period, he began to work with materials and corrosion, and later moved to piping and accessories technology, where he has become one of the lead technical advisors on valve issues. Correia was part of the task force that revised the IOGP S-562 standard, and wrote the S-611 standard. Correia has a master’s and a doctor’s degree in welding by the Universidade Federal de Uberlandia.