A key distinction between the consumer world and the industrial world is the power the latter might have over a manufacturer. An individual is not typically able to impose on their favorite cellphone supplier additional requirements addressing design and materials; but this is something commonly done for industrial valves. The bigger the end user, the greater the power. So, it should come as no surprise that oil companies not only have this type of power, but also exercise it with gusto. In other words, oil companies developed distinct supplementary requirements to improve valve safety and reliability. Unfortunately, the wide variety in these requirements poses a fantastic burden on manufacturers, which must read, understand, and create internal workflows to all of them. That is the problem that the IOGP (International Association of Oil & Gas Producers) is trying to solve, publishing standards that are an amalgamation of the individual requirements. Read on to learn more about what is being done and how it is affecting the valve industry.

By Davi Sampaio Correia, Technical Consultant

The Quest for Quality on Valves

Oil companies operate platforms, gas plants, refineries, and pipelines that are critical to modern life. Their facilities are normally kept running 24/7 and, given the volume and price of what is being produced, even small disruptions might cause the loss of millions of dollars in revenue. When dealing with oil, the cost of a valve is not its price tag at the manufacturer. The true price is the cost of potential down time. For example, shutting down a platform due to a gas leak through the stem packing, finding a replacement valve, putting said replacement in a helicopter or tugboat, paying expensive offshore labor to replace the old valve, and dealing with process instabilities during start-up quickly adds up. While this is not an exhaustive list, it provides an idea of how seriously oil companies must take valve quality – or any other equipment, for that matter.

Root cause analysis of many failures led oil companies worldwide to develop a comprehensive quality program for valves. This was often a multi-pronged approach, attacking issues from design to operation (for example, stringent supplier qualification and creation of maintenance procedures). One of these initiatives was born out of the belief that standards guiding valve design were sometimes silent or vague on many critical issues. Depending on the application, the lack of clear rules may or may not be a problem. Quality control of the elastomers used in a valve for sealing might be achieved via a manufacturer’s internal procedure or a recognizable international standard. If the application is cooling water, perhaps the former is sufficient. However, if similar elastomers are for a gas application, the end user might insist on the latter, due to the more severe consequences of failure.

Different companies have different quality philosophies, priorities, and resources. As a result, supplementary requirements range from general guidelines to exhaustive documents totaling hundreds of pages. Engineers working for valve manufacturers need time to get acquainted with the several requirements and to develop the internal procedures to guide employees on each of them. All this, of course, costs money, which must be incorporated in the final valve price. If all the different requirements could be harmonized in a series of standards, controlled by a single agent, who can provide easy access to revisions, that would be a huge step in reducing valve cost and expediting the procurement process. That is what the IOGP is currently doing.

What is the IOGP and JIP33?

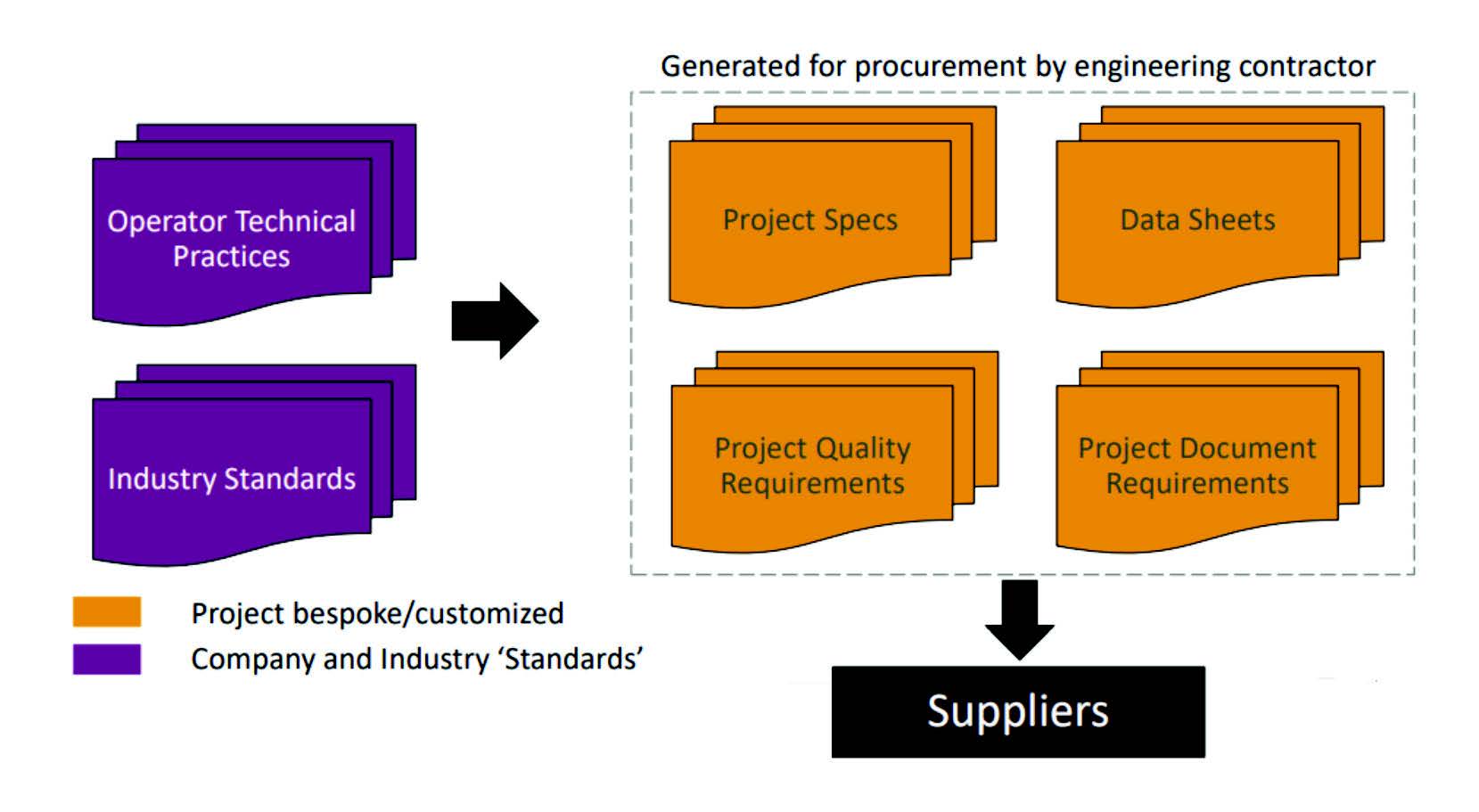

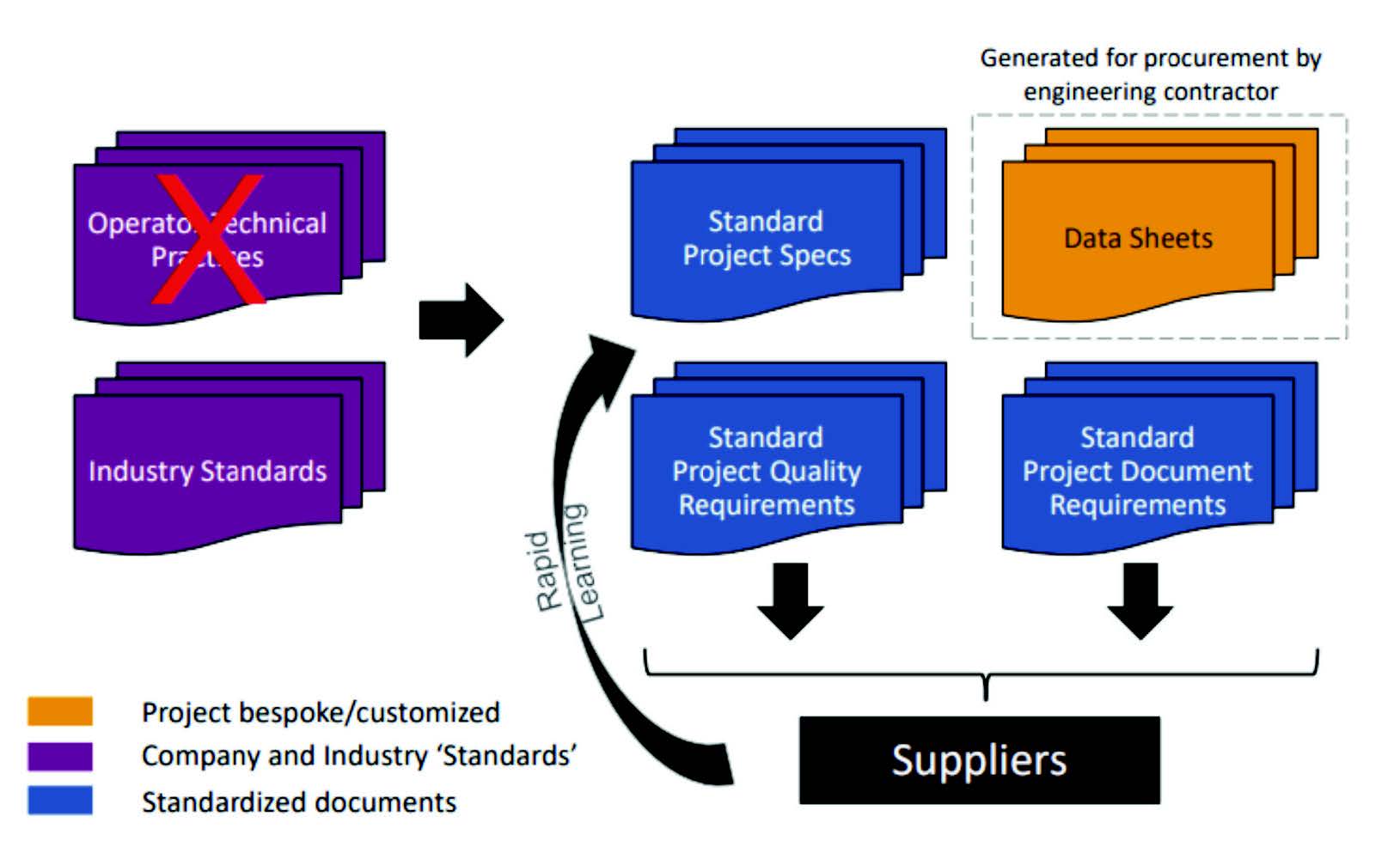

The World Economic Forum (WEF) is an independent, international, not-for-profit organization founded in 1971. Among its goals, is the improvement of the world economy. After commissioning a study on the Oil & Gas sector, the WEF came to believe that it could reduce costs and budget overruns with a standardization initiative. The WFE then approached the IOGP (International Association of Oil and Gas), an association tasked with improving safety and performance by sharing best practices. The IOGP currently has 78 members, which are responsible for the production of around 40% of the world’s oil and gas. In 2016, the WFE and the IOGP initiated the Joint Industry Programme 33 (JIP33), with the aim of harmonizing specifications for a series of equipment, to achieve a better, faster, and cheaper supply chain. Figure 1 presents flow diagrams comparing procurement methods before and after JIP33.1 More than 40 specifications have been published so far and there are more to come. These specifications cover equipment as diverse as diesel engines, batteries, and cranes; and the specifications are free and be down-loaded at the IOGP webpage.2 Regarding valves, the following documents can already be found:

• S-729 – Control Valves

• S-730 – Flanged Steel Pressure Relief Valves

• S-707 – Actuators for On-off Valves

• S-611 – Gate valves to API Spec 600/603

• S-562 – Ball Valves to API Spec 6D

• S-563 Material Data Sheets for Piping and Valve Components (See Figure 2)

• S-731 – Operator and Mounting Kits for Subsea and Pipeline Valves (API)

• S-708 – Subsea Pipeline Valves

• S-561 – Subsea Trees to API Spec 17D

It is important to highlight that each JIP33 specification is comprised of not one, but three documents:1

• A Supplementary Specification to an industry standard, such as the S-562, which is related to the API 6D. The supplementary specification contains the technical requirements that complement the parent standard (in this case, the API 6D).

• An Information Requirements Specification or “IRS”, that contains a list of pre-defined documents and data required to be delivered by the supplier.

• A Quality Requirements Specification or “QRS”, that contains the quality management system, inspection and testing activity.

As to the process of how the above documents were created, the approach consisted in first selecting a small subset of companies among the IOGP members. This subset sent several SMEs to a series of technical workshops, in which the contents of the individual companies’ requirements were compared and discussed.

Using a voting system, the SMEs produced a draft with the agreed requirements. The draft was then sent to manufacturers for feedback. For a requirement to move from draft to published document, the feedback from manufacturers had to be positive – or at least neutral – signaling that the requirement was technically feasible and within reason.

An Example of IOGP Document: the S-562

One of the most known IOGP standards regarding valves is the S-562 (Supplementary Requirements to API Specification 6D Ball Valves). As the title informs, the standard complements the API 6D rules for ball valves – and only ball valves, despite the fact that the API 6D covers not only ball, but also check, gate, and plug valves.

The S-562 was written as an overlay to the API 6D, following the section structure of the parent standard. That is, a API 6D is needed to make sense of the S-562. For every section of the API 6D, paragraphs can be added, replaced, or deleted. The S-562 also includes new requirements on sections that had previously not existed in the API 6D. If there is no mention of an API 6D section in the S-562, it means that there is no modification to it.

There are also action words through-out the length of the S-562 that instruct the reader on how to use the standard in relation to each section of the API 6D. For example, in section 5.1 of the API 6D (Design Standards and Calculations) the S-562 states that the second paragraph (including notes) must be replaced. In this case, the API 6D text says, in summary, that design must follow the rules of an internationally recognized code (some examples of such codes are given). The text from the S-562 that replaces the second paragraph is much longer and stricter. It limits the design codes for pressure-containing elements to the ASME B16.34 or the ASME BPVC Sec VIII Division 1 or Division 2; there are also nine additional paragraphs of instructions, such as what external loads shall be considered and how to perform bolt preload calculations.

Points Worth Considering

The IOGP documents modify their related parent standards to varying degrees. Continuing with the S-562 as an example, the second edition of this document (2019) has 118 pages, almost the same number as the parent standard (220 pages for the API 6D 24th edition, 2014). Although the new requirements introduced by the S-562 limits manufacturers’ creativity, the more stringent design rules, testing, and quality control, result in a valve with superior performance. Pricewise, anecdotal evidence points to no substantial cost increase, as the more stringent rules are counterbalanced by savings related to producing valves under a unified set of instructions.

However, there is still some controversy as to the full adoption of the IOGP standards – at least regarding the S-562 and the S-611 (gate valves). This is due to some members of the Oil & Gas industry believing that the old API 6D valves are good enough and that they do not need the extra hassle of the S-562.Another point that complicates matters is the transition period during revisions of the parent standard. For example, the S-562 from 2019 works with the 24th edition of the API6D. Recently, the API published the 25thedition (December 2021), which displays a different text sequence, Consequently, the 2019 edition of the S-562 no longer overlays the original text in the same manner and must be revised. This leads many to question how contracts for API 6D ball valves should proceed now? The added complexity for procurement will require expedite action from the part of the IOGP and further consideration into the future.

References

1. Adapted from https://razmahwata.fi les.wordpress. com/2019/12/jip33-industry-day-kl-public.pdf

2. https://www.iogp-jip33.org/library/#1593693286035-f9a446fe-4b2e

3. https://www.iogp.org/bookstore/product/s563v02/

About the Author

Davi Correia is a Senior Mechanical Engineer who has worked at a major Brazil-based oil company for the last 15 years. Correia is part of multi-disciplinary team that provides technical support for topside piping and equipment of production platforms. During this period, he began to work with materials and corrosion, and later moved to piping and accessories technology, where he has become one of the lead technical advisors on valve issues. Correia was part of the task force that revised the IOGP S-562 standard, and wrote the S-611 standard. Correia has a master’s and a doctor’s degree in welding by the Universidade Federal de Uberlandia.