Abrasive service valves too, can be characterized as critical service valves. They may not be as expensive as an ultra-high pressure drop, high temperature globe control valve, but their operating expense can be as high, or greater than, costly control valves.

By Todd Loudin, President North American Operations/V.P. Global Sales – Flowrox

To understand the valves that are utilized in abrasive services, it is necessary to review the options and consequences of those available options. There are several primary valves that can be selected and utilized in slurry service, including (but not limited to): ball, plug, butterfly, diaphragm, knife gates, and pinch valves.

Following selection, an engineer must analyze the slurry. If a process is handling 5% solids, then there are many choices; especially if the solids are not abrasive. However, if the slurry is abrasive, has scaling properties, and has a high solids content, then an engineer’s options become much more limited. After all, highly abrasive slurries, scaling properties, and severely abrasive slurries are reason for these valves to be placed into the critical service category.

Understanding Valve Selection

A true engineer or maintenance manager — especially in industries which rely on a high number of abrasive valves — understands the importance of adequate valve selection. When valves need to be repaired or replaced (usually every month, to every three months) this places them in the critical service category.

Some industry folks may even claim that replacing a valve is not the problem, as it may be standard practice to replace the technology every month to three months. Often though, this is done simply because it is inexpensive or because the standard operating procedure is to just replace the technology when it fails. In reality, settling for subpar service from a valve is never correct, as the cost of valves in a control loop may result in a payment of hundreds of thousands in operating expenses (OPEX), simply because they are (often wrongfully) deemed necessary.

The main failure points of valves in services that are highly abrasive, and have high solids content, and have scaling are where there are voids or cavities in the valve structures. As well, wetted parts that are subjected to this flow stream are potential areas for valve operational problems.

Lime: A Tricky Medium for ValvesLime slurry is utilized by numerous industries, though namely in: power generation, mining, chemical process, iron and steel, glass production, food and beverage, and water and waste-water operations. Lime slurry, or milk of lime, is very abrasive, and has the tendency to scale and harden in void areas. Lime does not dissolve in solution but is rather a suspended solid. For this reason, there is typically a lime slurry loop which is kept in constant motion to minimize scaling and hardening. Many valves however, may perform very poorly in lime slurry service. Attempts to utilize conventional soft seated or utility valves in lime slurry can result in frequent valve repairs and costly operating expenses.

When to Utilize Critical Service Valves

Lime slurry and copper concentrate are two of the most common slurries where these highly abrasion-resistant valves are required. Of course, copper concentrate is primarily found within the mining industry — and there are many other precious and semi-precious metal concentrates where these valves are also required.One significant consumer of slurry valves for lime slurry is the power industry. On a global scale, coal-fired power plants have had to reduce their harmful emissions, and many have installed flue gas desulphurization (FGD) units reduce these emissions. The FGD units add no power production but are an expensive option to reduce emissions.

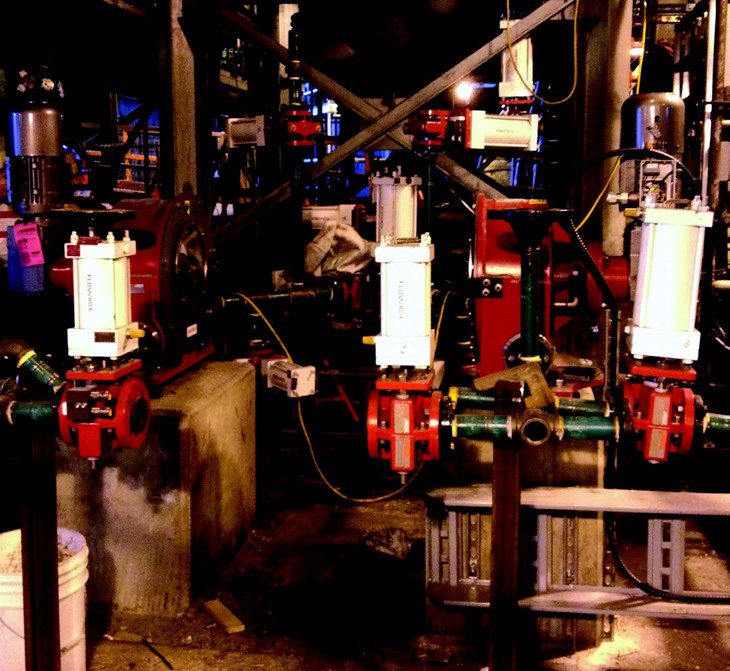

A 100 megawatt power plant may utilize several hundred control, automatic, and manual pinch valves. Also, condenser isolation may be accomplished in these power plants by 36”, 48”, and 54” heavy duty slurry knife gate valves. Certain FGD units have hydrocyclones for classification, and pinch valves have been an ideal alternative to slurry knife gates on hydrocyclones. The bank of valves at the top of the hydrocyclone are subject to spray from the swirling slurry below. Knife gates, valve gates, and operators become encrusted with dried minerals that inhibit valve operation. However, due to the enclosed nature of a pinch valve, the valves work flawlessly without jamming or difficult operation. As well, the rubber sleeves in the valves typically survive multiple years in service without repair.

Conclusion

Many of the valves that are ideal for clean services are not ideal for heavy slurries. Even general utility valves may have good survivability in 5 – 10% solids slurries, providing the slurry is not abrasive. When slurries become 20 – 80% abrasive (and may scale) an engineer should completely change their way of thinking in regards to valve selection. General positive characteristics of a valve that is suitable for these high solid content slurries are full port design, no pockets or cavities for material accumulation, limited stems or seals in contact with the flow, a valve that has self-cleaning properties, and finally, internal components that are highly abrasion-resistant. There are three types of valves that are best suited for heavy abrasive slurry service, the first of which is a metal seated ball valve with hardened ball and seats. Also, a scraping seat will to help remove scale build-up on the ball. Body cavity fillers or body cavity flushing may also help to improve valve MTBF.The next valve type that is workable is a heavy-duty slurry knife gate valve. This is not to be confused with a utility knife gate valve. Utility knife gates often have O-ring seals or wedge sealing. They can be used on lighter slurries that are not highly abrasive. Slurries, such as 5% pulp stock, are ideal for certain utility knife gates. However, when you get to the extremely high solids content and abrasive operations, one will require a true heavy duty slurry valve. This type of valve has very large rubber sleeves on the inlet and outlet of the valve. When the valve is in the open position, the rubber sleeves are the only parts in contact with the flowing medium. These rubber sleeves give this valve the ability to handle extreme abrasion. These valves are also push through style. The stainless steel gate, when closing, separates the rubber sleeves and forces any entrapped solids out the bottom of the valve into a cavity. That cavity can then be flushed with clean water to wash away the particles, or it can be left open to the atmosphere to discharge the solids and a small amount of liquid medium.

Finally, the best choice for extremely abrasive, scaling, and high solids content slurries is a high-quality pinch valve. Please however, be extremely cautious, as there are many low-quality pinch valves currently in the market. Those low-quality pinch valves typically have low-pressure capabilities and the rubber sleeves are often weakly reinforced. Highly engineered pinch valves will be capable of slurries up to 100 bar (1,500 psig) shut-off. The pinch valve has no pockets or cavities for material to accumulate within. The rubber sleeve is 100% full port and in the open position is just like an extension of the pipeline. It also is the only valve that is, by its very nature, self-cleaning. If scale has begun to form on the rubber sleeve, the valve begins to close as the rubber is flexed. This starts to flake the scale build-up. As the rubber sleeve closes, the velocity across from the sealing surface increases and pressure washes the inner surface clean. Therefore, the rubber sleeve is superb at withstanding abrasive slurries.

All three valve types have their advantages and disadvantages, but in general, they are the better choices for abrasive, scaling, high solids slurries — regardless of which industry you are in.

About the Author

Todd Loudin is the President of Flowrox North America and Vice President of Global Sales. He possesses a Bachelor of Sciences from Kent State University and an Executive MBA from Loyola. Todd has been with Flowrox for 26 years, and prior to that, he worked 5 years with Neles.