Located in the city of Glendale, only nine miles northwest from Downtown Phoenix, Ceretta Candy is celebrating its 50th anniversary of making French mints, marshmallow caramels, and almond bark, although the company has been creating these sweet treats from its current location for the past 29 years.

We were already looking forward to touring the factory floor to see for ourselves the many different ways components such as valves can be used throughout a candy manufacturing plant, but we were even more eager when we were told that all of the currently operating machinery date anywhere from the late 1920s until the late 1960s. In fact, they are the very same machines that the company began using when it first opened. Needleless to say we had many questions such as, ‘Do the machines not break down all the time?’ and ‘Where do you find replacement valves for the machines?’ Luckily for us, Ceretta Candy’s Esther Sorenson acted as our personal tour guide and she not only answered all of our questions but also gave us a thorough understanding of the importance of using stainless steel, especially for machinery components, throughout a factory such as this one.

We knew that we were getting close to the candy factory because we were guided by the delicious scent of chocolate

wafting in the air waving us on to our destination. This heavenly aroma only grew stronger as we opened the front door to the candy factory and entered the retail shop at the front of the building. What we saw before us was certainly a feast for the eyes (and the stomach): every flavour, shape, and size of chocolate you can imagine from milk to dark and wrapped in what seemed like hundreds of different kinds of wrappers from bright pink tin foil to clear plastic with sparkles. And that was just the individual chocolates! There were also chocolate bars, truffles, caramels, taffy, popcorn, bark, fudge, and so much more. I finally had an idea of what Charlie Bucket felt like when he first stepped

inside Willy Wonka’s chocolate factory.

When we were able to tear our eyes away from the prepared candy, we looked past the retail shop and onto the factory floor, which seemed to be divided into several different sections. That was when Esther came towards us, introduced herself, and began the tour by sharing a short history on the family-run business. “Mr. Jim Ceretta was originally from Canton, Ohio and in 1933 he began learning the candy making business from his father-in-law.

In 1968 Mr. Ceretta moved his wife and eight children from Ohio to Arizona. The company was first located in Phoenix before moving to its permanent Glendale location in 1989. As the children grew older they helped their father with the business and you’ll see their names painted on the walls,” explained Esther.

She continued, “Jim Junior ran the Caramel Kitchen until his retirement last year and now Wyatt, Cheryl, and Cole

have taken over for him. Joe was in charge of all of our crème centers and taffy before he retired last year but now Wyatt is all looking after all that. Jerry ‘The Chocolate Man’ and his son Tony are in charge of our French mints, which we are famous for.”

Avoiding Product Obsolescence

Esther then led us to the farthest end of the factory, named the Caramel Kitchen. What really stood out about this section was that it was almost completely clad in stainless steel, from the cabinets to the sinks to the tables. Esther stated that the majority of this stainless steel was from the 300-series because it provided the right amount of corrosion resistance, heat resistance, sanitation and affordability.

She continued to explain some of the other uses for stainless steel in the caramel kitchen, “There is a great big stainless steel tank that holds approximately 80,000 gallons of corn syrup and when we make caramels we pour about 80 pounds of that syrup into big copper kettles located at the back of the kitchen.

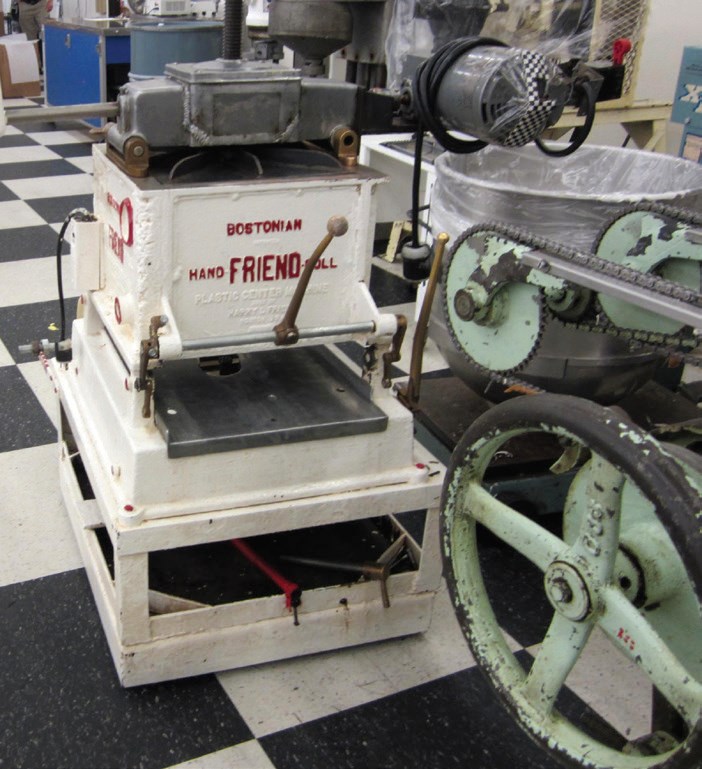

Those kettles cook the syrup with milk, butter and sugar to about 225 degrees, which will take about an hour. That mixture will then get poured out onto a sterile 316-stainless steel surface to cool. My co-worker Cheryl is now cutting a completely cool caramel slab into long strips with an extremely sharp stainless steel knife. She will bring those caramel strips over to this white and red Friend machine to do two things. First: a 400-series stainless steel blade will cut the ropes into bite-sized pieces, and second: this white part here will wrap the caramel in cellophane. The wrapped caramel will come out of this medium sized valve that is attached to the outside of the machine and into the box below. This machine can wrap 130 candies per minute and can also wrap English toffee, popcorn, and chocolate turtles.”

When asked how old this particular machine is Esther answered it is from the early 1950s, however they have several

other working Friend machines on the factory floor that are even older. She clarified that the reasoning behind using these older machines is partly the old adage “Why fix what isn’t broke?” and also that the quality of the candy is always consistent on these machines.

Even though when these machines where made, they built to last, that doesn’t mean that they will work forever, parts do wear out, valves included. Thankfully it never turns into a terrible situation because they have a repair specialist on call that can create cast new valves so part obsolescence is never an issue. Esther confirmed that new valves are needed to be created every few years or so, but routine repairs are also strictly performed on all the machines to make sure they are in their best working order at all times.

Another machine located in the Caramel Kitchen is the White Light, which is actually a chocolate enrober; that is, it covers objects in chocolate. This large, but surprisingly quiet machine is constructed out of many stainless steel parts such as valves and conveyer belts. The White Light takes about an hour to heat up to 225 degrees, thus being able to melt chocolate or pastel. During our tour we were lucky enough to see this machine in action, covering pretzel sticks in white pastel (which is a delicious and all natural substance similar to white chocolate). It was really neat to watch the stainless steel parts working together to move the conveyer belt full of salty pretzels under a thick waterfall of white pastel. After each pretzel was covered, the machine is temporarily stopped so all the pretzels can be covered in sprinkles.

Production on the Factory Floor

After being lured away from the White Light and the Caramel Kitchen with pretzel and caramel samples, we followed Esther into the crème center area of the factory, which like the Caramel Kitchen, was gleaming in all its stainless steel glory. Esther detailed that the actual crème centers are made first in a big copper machine called a Vacuum Cooker. The crème mixture gets very hot in these cookers and then they are poured into a huge stainless steel tank to get thoroughly stirred. Esther pointed out another white and red Friend machine, but this one was considerably smaller and slightly older looking. This particular machine was made in 1929 and was one of the very first machines that Jim Ceretta bought when he was learning the candy trade. The crème centers are rolled out on this machine and then a stainless steel stamp punches out a crème center shape. Then all the stamped out crème centers cool on a stainless steel rack before going through an enrober and then they are put through another Friend machine that will wrap them.

With all of the machines being anywhere from 50 to 89 years old and working almost every day, it really is essential that the company does have someone on call to be able to come in and replace parts or repair a machine as soon as possible. Having a machine down for a down or several days just isn’t an option.

Esther then led us towards what was arguably the largest machine, taking up most of the space on the factory floor. She explained this was where the most popular and bestselling chocolate was made: the French mint, a cool mint flavoured chocolate wrapped in luscious milk chocolate. The French mints weren’t being made when we were there but Esther walked us through the complex process. It all begins with a mould made up of 32 deep sections. Green pastel is melted in a huge stainless steel tank before being poured into the mould, which is then cooled in a chamber. Then the mould goes through the machine, which has a rectangular stainless steel tank of melted French mint flavoured chocolate. The machine will then deposit the French mint chocolate into the mould—32 deposits every 30 seconds while the machine is running. The u-shaped machine has built-in coolers that will cool the chocolate. When they are cool enough, they will be wrapped on a German machine made in 1969 that can impressively wrap 1,000 pieces of candy per minute.

As we slowly wound our through the factory floor past the walls, tanks, and moulds of stainless steel back towards the retail shop at the front of the building, Esther stops us by a huge box reading Guittard Company and shares, “This is where we get our chocolate from and they make the chocolate based on Mr. Ceretta’s own private blend. They ship us the chocolate in huge 10-pound bars. Each of these boxes weighs approximately 1,500 pounds. During our peak season (around Easter) we can go through 2-3 boxes a day, producing 3,000 pounds or more of chocolate a day. Each year we go through 780,000 pounds of chocolate and that’s not even counting all the milk, butter or sugar we also go through!”

We ended our fascinating tour by thanking Esther for her time and for showing us around the factory floor. It was a great experience to learn how stainless steel can be used in an industrial food factory as well as how older machines can still work just as well as newer ones if properly maintained. Ceretta Candy also holds free tours for the public so if you are ever in the Glendale area, stop by for a tour and a candy or two!