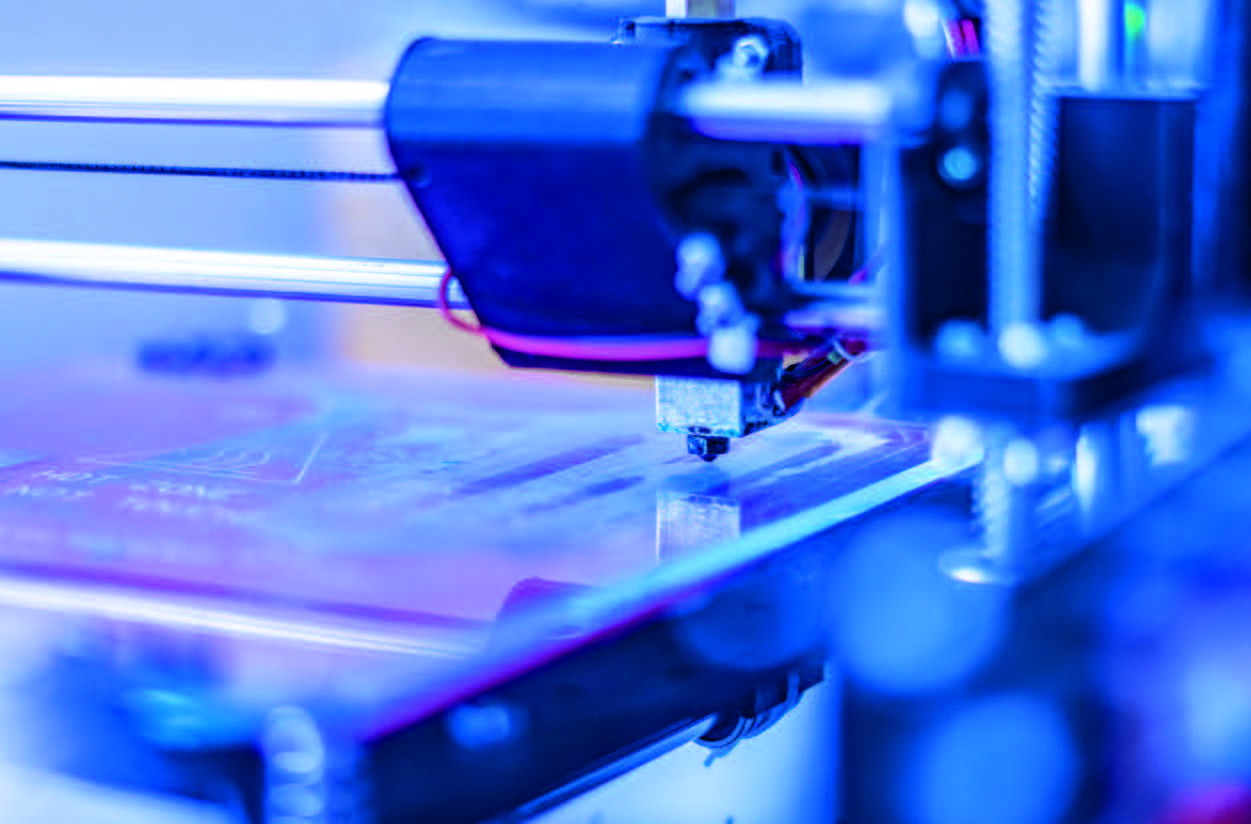

Additive manufacturing technologies represent the future for various industries, including but not limited to: aerospace, medicine, transportation, energy, and consumer products. Many industries have already made additive manufacturing a major part of their day-to-day operations, while others are just beginning to experiment with this revolutionary technology. Additive manufacturing, also known as 3D printing, manufacture quickly and precisely objects that are made of metals or polymers by printing them layer by layer, as opposed to machine them out from a large piece of raw material. In the oil & gas industry and the valve manufacturing industry, additive manufacturing is starting to make its debut. While not without hurdles and roadblocks, this technology is extremely promising.

Valve World Americas had the pleasure of speaking with Carlo De Bernardi, Staff Valve Engineer – Global Production, about how ConocoPhillips, one of the world’s largest independent E&P companies, is making additive manufacturing a top priority in its future plans.

By Angelica Pajkovic and Sarah Bradley

The Valve Expert

Carlo De Bernardi’s career path has been full of twists and turns, making him an expert not only in valves, but also in adaptability. By degree, he is a Civil Engineer, but at ConocoPhillips, his focus is much more centered on mechanical engineering. In his 20s, De Bernardi wanted to travel, and in 2001 settled into a position with Cameron, a Schlumberger company, at one of the largest valve manufacturing facilities in the world, near his hometown in northern Italy. This role promised that his job would involve travel, and that is what convinced him to begin his career in the valve industry. “Once you are in the valve industry, there is no way out,” he said. He worked for Cameron for more than a decade, before being hired at ConocoPhillips in 2013.

Now a long-time employee of ConocoPhillips, De Bernardi works in the Global Production department, with a specific focus on valves. Day-to-day, half of De Bernardi’s role is focused on supporting operations, supporting projects, managing the approved vendor list, and of course, troubleshooting all valve-related problems. While he enjoys supporting different projects, De Bernardi admits that it can be quite stressful, especially in the current global climate: “We are living in such a changing landscape, and that is becoming quite stressful as we must keep adapting. Being adaptable is, I would say, the key to not only survive, but to thrive in this environment.”

In addition to his focus on valves, De Bernardi spends a large portion of his time working with additive manufacturing. “I would say that approximately 50% of my job is valve support. The other 50% is focused on additive manufacturing,” he explained. De Bernardi first began researching additive manufacturing approximately six years ago, and it has since become a major focus in his role.

Additive Manufacturing: What are the Obstacles?

3D printing technologies are still relatively new to the oil & gas industry, and for companies like ConocoPhillips, this means that extensive testing and quality control measures are required before this technology can be implemented in any meaningful and wide scale way. The main difference between 3D printed materials versus forgings and castings, is that forgings and castings are anisotropic in terms of mechanical properties, while 3D printed materials are isotropic. “Filtering and analyzing the data is key. Right now, we are learning as an industry how to do it,” said De Bernardi.

Given that standardization is one of the main goals of both the oil and gas and the valve industries, one can understand the unique potential and challenges that additive manufacturing simultaneously poses; casting and forging evolves at a steady pace, making standardization across the industry relatively simple. Additive manufacturing technology, on the other hand, evolves at a very fast pace, making standardization more expensive. “An industrial metal 3D printer can costs millions of dollars. Understandably, some companies are hesitant to make this kind of investment with what they may feel is insufficient data,” explained De Bernardi. “Standardization is key to keeping companies moving efficiently, and for ensuring consistency and reliability in products. Valves are one of the first applications that we, as an Industry, are evaluating through a lens of standardization via 3D printing.”

The only solution to this user’s hesitancy is to actually utilize the technology. “I recommend more field trials. Through data analysis and further testing, ConocoPhillips hopes to find a way to circumvent these hurdles of 3D printing,” he continued.

Additive Manufacturing: What are the Possibilities?

De Bernardi spearheaded the creation of the API Standard 20S task group, which is entirely dedicated to researching and trialling “additively manufactured metallic components for use in the petroleum and natural gas industries.” De Bernardi is one of ConocoPhillips’ strongest advocates for the future of additive manufacturing, as “the potential of this technology is, in my opinion, extremely significant.”

According to ISO/ASTM standards, there are seven different types of additive technology. When asked which additive manufacturing technologies he believes are the most promising for oil & gas for the purpose of metallurgy, De Bernardi replied that there are three specific technologies which are frequently used methods: Powder Bed Fusion (PBF), Directed Energy Deposition (DED), and Binder Jetting (BJT).

In PBF, powdered metal is fused together using an energy source, typically a laser or electron beam. PBF is one of the most utilized technologies because it is very controlled and very precise; its main limitations are the speed of printing and the size of the product that it can print. In Directed Energy Deposition, metal powder or wire is fed into a meltpool created by a laser or electron beam in a process similar to welding. It is a robotic type of welding that is more controlled than traditional robotic welding, but the basic concept is the same. While, virtually, there are no limitations in size, there are limitations in resolution with this type of technology. Finally, binder jetting is the newest technology, and involves the 3D printing of hard metals. A binding agent deposited onto powdered metal or sand creates the geometry and is typically followed by sintering to fuse the powder.

“If the evolution of technology in the oil & gas industry continues, we can expect the objects produced in this manner to be of better quality, higher repeatability, and lower cost,” said De Bernardi. Although the aerospace industry is currently leading in the additive manufacturing market, the potential cost benefit to the oil & gas industry would be significant. “One major potential improvement that I am excited about is the impact that 3D printing could have on current supply chain issues. Right now, the supply chain is linear, but with additive manufacturing, it could become circular, and therefore more accessible to manufacturers and consumers,” he explained. “If you think of a print bed, that is the area where all the printing is happening, you do not need to print 100 of the same objects to reach any type of efficiency, you can print 20 different objects at the same time just to optimize the print bed; that is not doable with traditional manufacturing.” This system of 3D printing would allow companies to minimize the number of physical spare parts that they have in stock, as they would be able to produce the necessary parts on demand and close to the point of utilization.

With valves, many manufacturers have begun to 3D print the control element of their control valves. Some valves have very complicated castings from a manufacturing perspective, so every time you have to cast multiple components and join them together, it is a time-consuming and expensive task. With additive manufacturing, you can combine many components in one. “Investing in new technology like 3D printing is not really investing in machines, it is investing in knowledge,” he said.

Case Studies

Some data analysis and testing of additive manufacturing has already taken place at ConocoPhillips. The ConocoPhillips team in Alaska recently 3D printed choke valves cages, which are flow control devices used in water injection wells. “They identified numerous choke valves that had become obsolete by the OEM. The solution was to retrofit the existing valve bodies with 3D printed valve cages made of Inconel 718. We will be able to extend the life of the choke valves using an optimized design,” he explained. “Using additive manufacturing, the engineers were able to resolve the problem without having to source, locate, and purchase a whole new fitted valve.”

Looking Ahead

According to De Bernardi, the sky is the limit for what is to come in the additive manufacturing industry. He believes that first and foremost, this technology can benefit both operators and manufacturers: “Being an operator, we need our manufacturers and we do not want to do their job. However, we want to enable our manufacturers to make things better. Additive manufacturing can make control valves more efficient because it is possible to make geometries that are not possible with traditional manufacturing; it also enables the prototyping of new products to be much quicker,” he said. “Additive manufacturing takes away the margin of human error since you are not welding things together.”

There is a lot of excitement in the Industry around the concept of “Digital Inventory” that can be summarized as the ecosystem to enable the just-in-time manufacturing of spares through an authorized network of equipment OEM and additive manufacturers. This approach will boost the adoption of the AM technology in our Industry and will potentially benefit significantly all parties by drastically reducing the inefficiencies of the traditional supply chain model.

De Bernardi expects 3D printing to be widespread in few years. “It is a combination of demand, and the technical time to do testing and then collect and analyze data. Once that data is compiled, the future of additive manufacturing in the industry is certainly bright,” he concluded.